Sensing for Continuum Robots - Part 2

Today, we continue our introduction to sensing the state of a continuum robot. If you have missed Part I of the intro, look at last week’s blog post before you continue here!

To sense information about the state of a continuum robot, it may be desirable to not integrate sensors to the robot, but to use readily available external sensing methods.

External Sensors

The most common external sensing means for continuum robots are coordinate measurements using mechanical or laser probes and image-based techniques.

Coordinate Measurement

A coordinate measuring machine/arm is used to measure the geometry of the robot by sensing discrete points on its surface using a probe. There exist two common types of probes typically used for continuum robots: mechanical probes and laser probes.

Mechanical Probes: To acquire a measurement point, the robot has to be touched with the probe of the measurement arm which is usually operated manually by a user. This technique is suited to measure the position of the tip of the robot or to gather information on the shape of robot by measuring at multiple distinct locations along it.

Mechanical probes provide high accuracies - usually sub-millimetre, but as operation is user-dependent the accuracy can vary. Mechanical probes are fast to setup and ready to use. But as the robot needs to be touched, it is challenging to not deform the robot while touching, which would lead to measurement errors and inconsistencies. As we are mostly interested in obtaining information about the centreline of the robot when we want to infer the shape, a coordinate measurement on the surface of the robot is suboptimal as it induces an offset to the centreline which has to be corrected for in post-processing. Lastly, mechanical probes for coordinate measurement are only suitable for static robot configurations and requires direct access to the robot.

Mechanical probes provide high accuracies - usually sub-millimetre, but as operation is user-dependent the accuracy can vary. Mechanical probes are fast to setup and ready to use. But as the robot needs to be touched, it is challenging to not deform the robot while touching, which would lead to measurement errors and inconsistencies. As we are mostly interested in obtaining information about the centreline of the robot when we want to infer the shape, a coordinate measurement on the surface of the robot is suboptimal as it induces an offset to the centreline which has to be corrected for in post-processing. Lastly, mechanical probes for coordinate measurement are only suitable for static robot configurations and requires direct access to the robot.

Laser Probes: To overcome the necessity of touching the robot for measuring coordinates, touch-less laser probes can be used, also referred to as 3D laser scanners. The laser probe is attached to the measurement arm and manually guided by the operator along the continuum robot. The laser probe emits a laser line and using the images from the camera within the probe, the distance of the scanned object from the probe can be determined. By sweeping the continuum robot, a point cloud of its structure can be obtained. This raw point cloud usually includes some noise as well as unwanted objects. Therefore, a post-processing step is performed to clean the data and eventually thin the point cloud in order to extract the shape.

Laser scanning has the advantage of providing dense information on the robot’s shape with contact-less acquisition. The precision of laser scanners is usually in the order of micrometers. This measurement technique is only suited for static cases, i.e., the continuum robot cannot move. Acquisition of the point cloud and post-processing can be quite time consuming. Lastly, this method also required direct line-of-sight, such that the continuum has to operate in free space.

Image-based Sensing

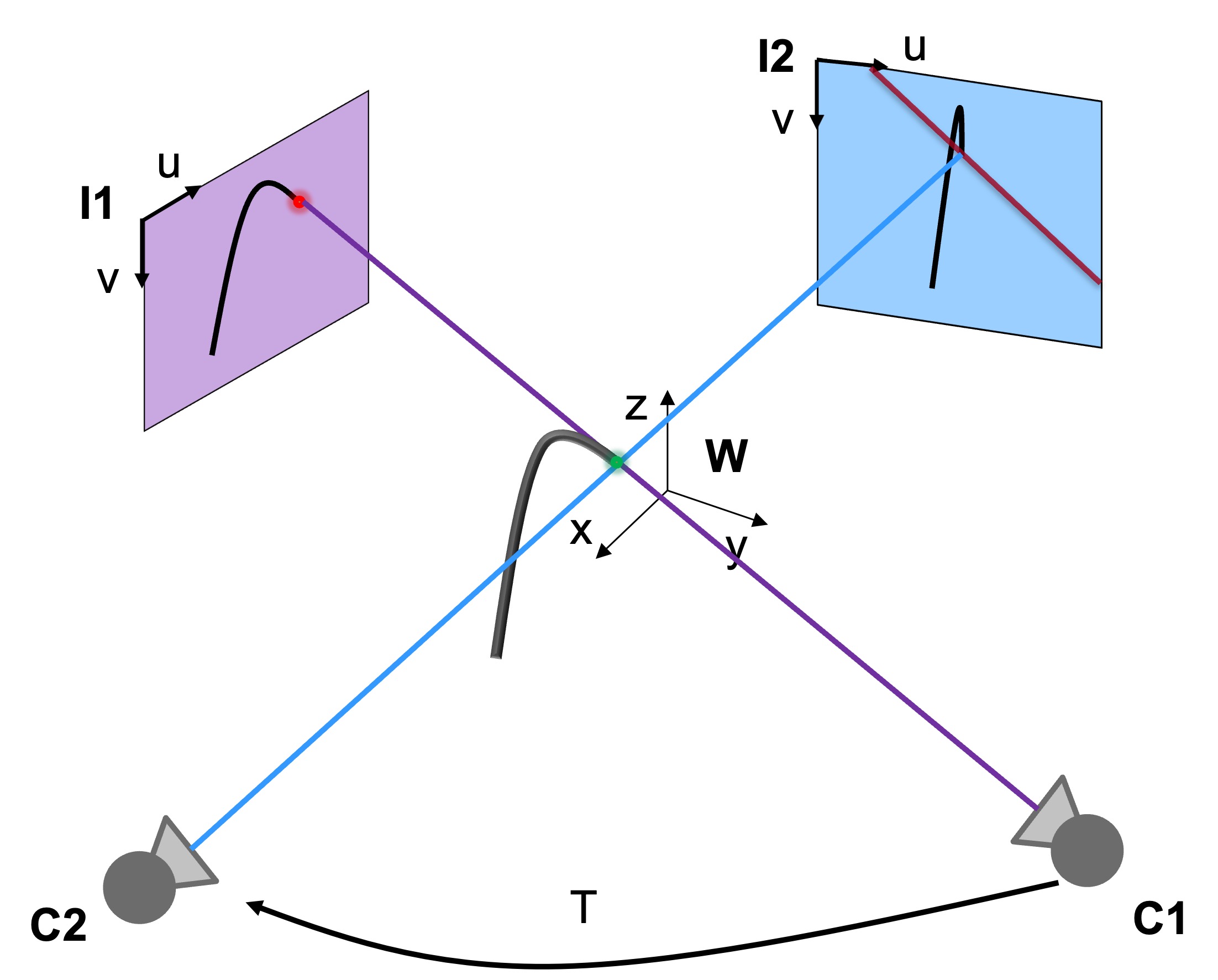

Image-based sensing employs mono- or stereoscopic cameras observing the robot fully or partially in its workspace. In robotics, an external camera is also referred to as eye-to-hand configuration. Using cameras observing the robot can be simply used to acquire image or video footage of robot motion in a qualitative manner, but it is more often applied to obtain quantitative measures. This requires additional processing of the images or video frames. Methods of computer vision, such as segmentation, 3D reconstruction using epipolar geometry, etc. are deployed to infer information on the robot’s tip position or pose as well as its shape. This information can then be used for visual servoing, also known as vision-based control, to control the motion of the continuum robot.

|

| The shape of a continuum robot can be resonstructed using two cameras and epipolar geometry. Corresponding image coordinates representing a point on the robot have to be identified in both images, to determine the spatial position. |

The image or video-stream processing is dependent on the desired information but usually involves multiple steps. This is particularly challenging for small-scale continuum robots as the information in the image representing the robot in terms of pixels is sparse. Consequently, the resolution of the camera and the lens have to chosen wisely. While using artificial markers on the robot to ease image processing may be appealing, this becomes infeasible if the robot has very small diameter. In recent years, the continuum robotics community has seen some efforts in learning-based image processing, but the majority of techniques relies on classical computer vision.

External image-based sensing has the advantage of being contact-less, such that it can be deployed both for static and dynamic continuum robot applications. Cameras are readily available and 3D reconstruction from stereo or multiple cameras can be highly precise (sub-millimetre). Nevertheless, processing of images in real-time or reliable reconstruction are challenging and usually not working off-the-shelf. If considering dynamic measurement, synchronization of the image acquisition needs to be accounted for. A downside of image-based techniques is that direct line-of-sight is required, such that occlusions or partial views have to be avoided and accounted for in processing.

Challenges

Ideally, one would want to use as many sensors as possible and probably combine different modalities for their strengths while mitigating their limitations. Yet, it is impossible to have a multitude of sensors in a continuum robot given that there are many challenges in electronics, sensor size and space, wiring, powering, system integration, data communication and processing. Therefore, a smart sensor design and configuration strategy is needed to keep the number of sensors required to achieve a desired sensing capability low, and to optimize the sensor configuration for the best performance. Developing a sensor configuration strategy for continuum robots is particularly challenging because of their deformable body and high number of DOFs.

As of now, there is no way to directly measure forces and moments acting on a continuum robot. This information has to be inferred from other sensing modalities as discrete strain information. Force/torque sensors are commonly used in rigid-link robots but may not be available at small enough scale. One way to approach this is by measuring the actual shape of a continuum robot, for instance from images, EM tracking, or FGBs, and then comparing the measured shape with the expected shape from the robot’s kinematic or kinetostatic model. The observed deformation is a result from external forces and moments acting on the robot (assuming that the model is accurate). With assumptions on where forces/moments are acting (e.g. just at the tip), the model can be used to estimate those. While this is working in principal, the technique is still subject of ongoing research.

We have looked at the most prominent sensors used for continuum robots. Considering soft continuum robots, the development and integration of flexible and stretchable sensors is even more challenging. For instance, highly stretchable strain gauges composed of liquid metal micro channels can be directly embedded into the body of a silicone-based pneumatic actuator. They can then be used to measure the bending angle of the actuator. Yet, as soft continuum robots undergo large deformations, selecting the number of strain gauges, their location as well sensitivity is far from trivial.

Some areas of open research are concerned with continuous, real-time shape measurements of variable curvature, multi-section continuum robots, continuous force measurements along the robot’s body, and tactile sensing skins.

Sensing in a Nutshell

As continuum robots are flexible bending/extending structures, sensing can be quite a challenge. The smaller the size of the continuum robot, the more challenging the sensor selection and its integration becomes. In our Sensing 101 Part 1 and Part 2 blog posts, we have seen that multiple sensing modalities exist, each of which has its advantages and challenges. As no measurement technique is perfect and as no sensing modality suits all needs, the selection of sensors is a trade-off between application requirements and the particular continuum robot.

Some application areas, such as surgery, may also provide additional sensing means, such as medical imaging to reason about the position/pose or shape of a continuum robot operating within the human body (ultrasound, fluoroscopy, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging). At the same time, applications may impose restrictions on which sensing modalities can be used. Think of a continuum robot for non-destructive inspection of a jet engine. Electromagnetic tracking would not be feasible in terms of range and external cameras would have no line-of-sight.