Concentric Tube Continuum Robots

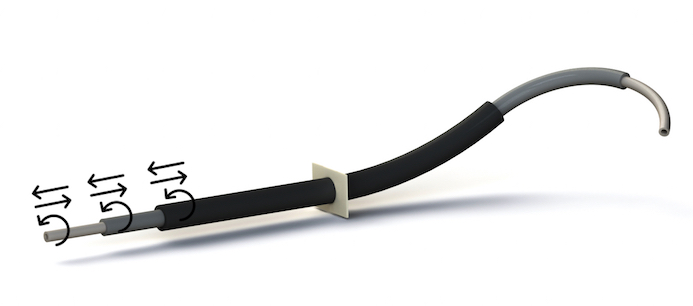

Tubular continuum robots or concentric tube continuum robots (CTCR) are the smallest among all continuum robots with typical diameter to length ratios of 1:250. The composition of concentrically arranged elastic tubes with pre-curvatures allows for simple, yet dextrous, robotic manipulators at a millimetre scale. Actuation is achieved mechanically by relative rotation and axial translation of the tubes and results in tentacle-like motions. CTCR are particularly promising for medical interventions, such as diagnosis through natural orifices or minimally invasive surgery. In today’s post, we review the general structure of CTCR and look into the motion capabilities and underlying mechanics.

General Design

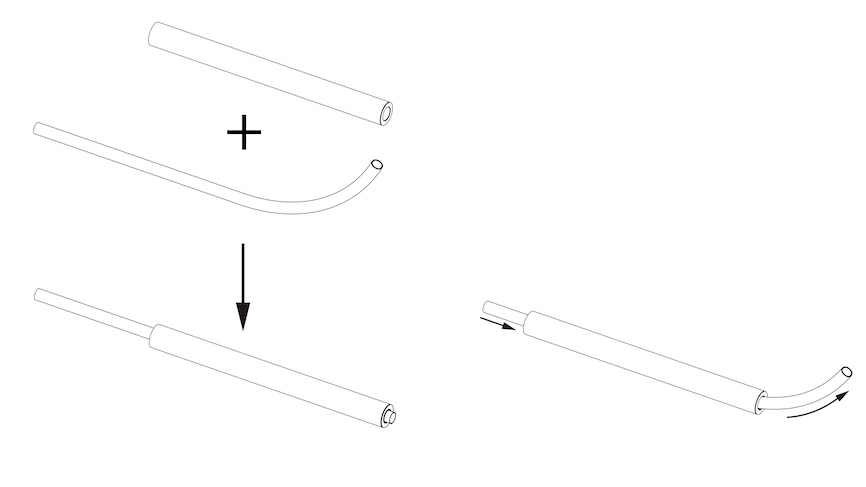

This type of continuum robot design relies on a backbone composed of multiple concentric compliant tubes. The tubes are free to move (translate and rotate) with respect to each other (subject to hardware limits) with the translations and rotations actuated at the base of the robot. The net effect is similar to a telescope: the structure canextend and contract by translational sliding of the tubes. To achieve more complex motions than a simple telescope, pre-curved compliant tubes are used. The tubes can be directly controlled in terms of extension and contraction as well as their relative rotation in respect to one another.

The achievable range of curvatures of the continuum robot are defined by the elastic interaction of the pre-curved tubes as they conform to an equilibrium state. In principle, each of the component tubes can have an arbitrary precurvature. Most commonly, each tube is either straight or precurved with planar constant curvature, or a combination of a straight section followed by a constant curvature section.

NiTi (nickel titanium, also Nitinol) is a shape memory alloy and most commonly used as tube material for CTCR. NiTi alloys have two unique properties: the shape memory effect and superelasticity. CTCR are based on superelasticity, which is the ability for the metal to undergo large deformations and immediately return to its undeformed shape upon removal of the external load. NiTi can deform 10-30 times as much as ordinary metals and return to its original shape. NiTi is also preferable for CTCR as it is highly biocompatible and therefore safe to use in medical robotics applications.

CTCR are typically composed of \(n \geq 2\) (typically 3), precurved superelastic tubes, which are inserted into one another. Each tube is mechanically actuated and fixed in an actuation unit at the robot’s base. Consequently, when designing a CTCR, one has to consider two main aspects:

- Selection of tube properties (curvatures, lengths, diameters, number of tubes) based on application requirements.

- Construction of a suitable actuation unit that grasps the tubes at their respective bases and applies telescopic and axial rotation motion to each.

We will explore optimal tube parameter selection and actuation unit design for CTCR in future blog posts!

Motion Capabilities

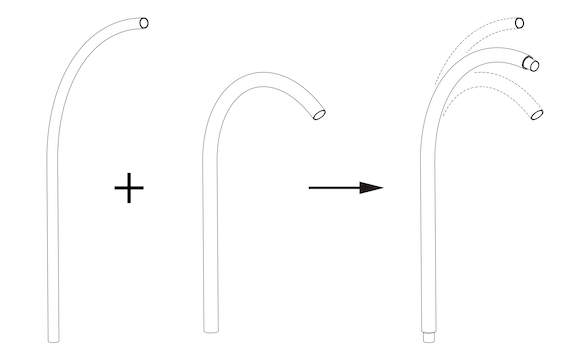

If multiple precurved tubes are placed concentrically, their curvatures will interfere with one another, causing bending and making the combined shape different from the natural shapes of the individual tubes. It is this interference effect, combined with both rotation and extension/retraction of the tubes, that we use to change the shape of the CTCR and create motion.

To understand the motion capabilities of CTCR, it is useful to consider the interaction of two concentrically combined tubes. Limiting cases of their interaction correspond to when the ratio of bending stiffnesses for the two tubes is either very large, such that the shape of one tube dominates that of the other, or the ratio is approximately one, such that the tubes’ shapes interact equally to determine the overall shape. We refer to these cases as dominating stiffness pair and balanced stiffness pair.

|

| Dominating Stiffness Pair: Since the bending stiffness of one tube is much larger than that of the other, the pair of concentric tubes conforms to the curvature of the stiffer tube. When the more flexible tube is translated such that it extends beyond the end of the stiff tube, the extended portion relaxes to its original curvature. |

|

| Balanced Stiffness Pair: The tubes are of similar stiffness such that their unstressed curvatures interact to determine their combined curvature. Relative rotation of the tubes causes the combined curvature to vary. |

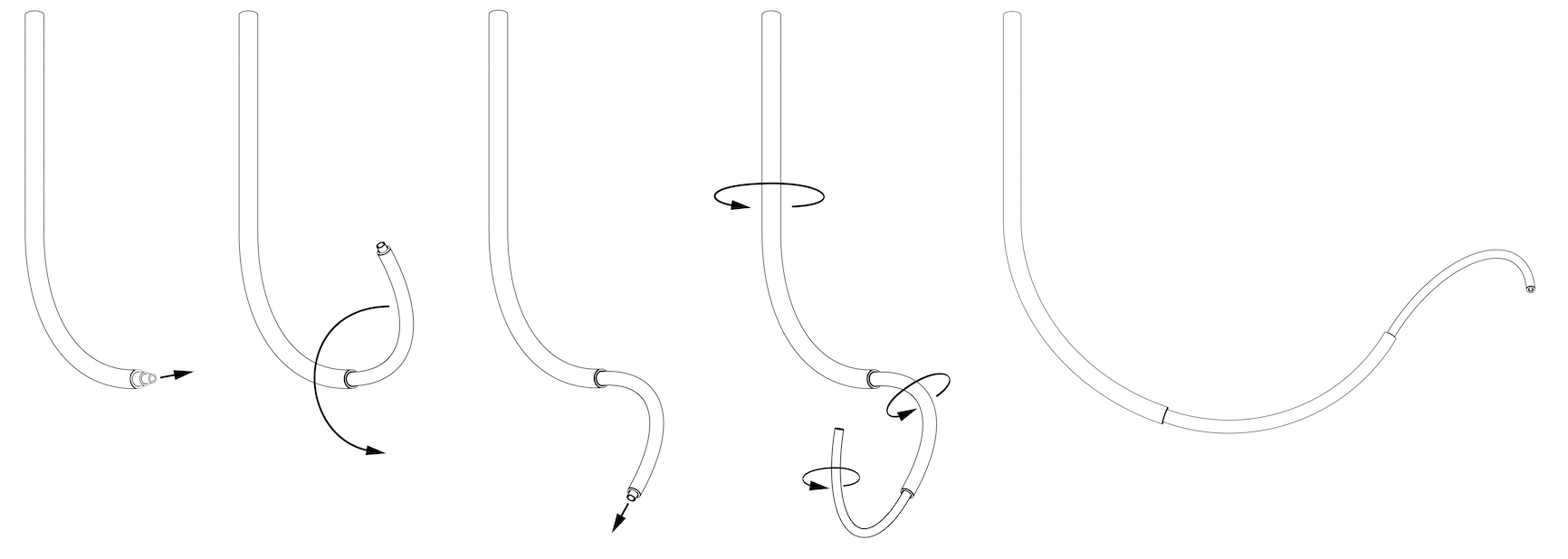

A CTCR usually combines multiple tubes with either pair type. The relative displacements of the tubes and their axial rotation are then determining the resulting shape. The tubes interact elastically and make one another bend and twist.

|

| Motion sequence of a CTCR composed of 3 tubes. Initially all three tubes are aligned (left). The middle and inner tube are then extended and rotated axially by the same angle. The innermost tube is then further extended. As all tubes can be axially rotated and extended/contracted, a multitude of possible shapes is attainable. |

Remarks

A challenge of CTCR is inherent to their design. Torsional deformation caused by relative rotation of the precurved tubes is an unavoidable phenomenon. The transmission of the rotation angle at the base of a tube to its tip may lag due to this phenomenon. More importantly, torsion may also cause structural instability. The energy stored in a CTCR usually has one minimum energy point, which determines the equilibrium conformation of the combined tubes. Under certain conditions, there exists more than one minimum energy point. The CTCR can abruptly move from one minimum energy point to another during operation. This is commonly refered to as the snapping problem. It has been known since early prototypes were constructed that with curvatures that are sufficiently high or tubes which are sufficiently long, rapid snapping motion can arise with rotational actuation of the tubes. We will look into means to address this challenge in future blog posts!

Further Reading: Cannot wait for our next blog post on concentric tube continuum robots? These review articles1 2 3 offer a great overview suitable for beginners!

References

-

H.B. Gilbert, D.C. Rucker, R.J. Webster III: Concentric Tube Robots: The State of the Art and Future Directions. International Symposium on Robotics Research, pp. 253–269, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28872-7_15. ↩

-

A.W. Mahoney, H.B. Gilbert, R.J. Webster III: A Review of Concentric Tube Robots: Modeling, Control, Design, Planning, and Sensing. The Encyclopedia of Medical Robotics, Chapter 7, pp. 181-202, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789813232266_0007 ↩

-

Z. Mitros, S.M.H. Sadati, R. Henry, L. Da Cruz, C. Bergeles: From Theoretical Work to Clinical Translation: Progress in Concentric Tube Robots. Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems, 5:1, 335-359, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-control-042920-014147 ↩