Motion Primitives

What are the motion capabilities of a continuum robot?

The ultimate goal of continuum robotics is to have a continuously bending manipulator such that its shape is fully controllable. Ideally, such a robot would be appearing as a flexible cylindrical structure of soft material with its current state dictated by infinitely many actuators. Three main challenges are associated with this idealized continuum robot:

-

From a mechanical standpoint, the design space to achieve continuously bending structures and compliance is very large.

-

Design of robots in absence of rigid elements is unfamiliar as the vast majority of existing robots is rigid, stiff, and well defined.

-

While a continuum structure may in principle have an infinite number of degrees of freedom in that it can bend, twist, contract, and eventually shear at any point along it, we will only be able to control a finite number of degrees of freedom by actuators.

Defining Feature

The defining feature of a continuum robot is a continuously curving core structure, often referred to as backbone, whose shape can be actuated in some way. An almost universal additional property is that the backbone is compliant; that is, it yields smoothly to externally applied loads. Such a continuous structure has an infinite dimensional configuration or shape space - at least in principle. In fact, only a finite number of degrees of freedom (DOF) are controllable/actuatable due to mechanical constraints in building continuum robots. If a continuum robot is controlled discretely (restricting the allowable shapes of the robot to a finite set, or a shape set defined by a finite set of inputs) then it will not only be much easier to realize from a mechanical standpoint, but also be much easier to control. Nevertheless, the compliance inherent in the continuum structure still allows the robot to adapt to contact with its environment and to compensate for the limitations in its actuatable degrees of freedom.

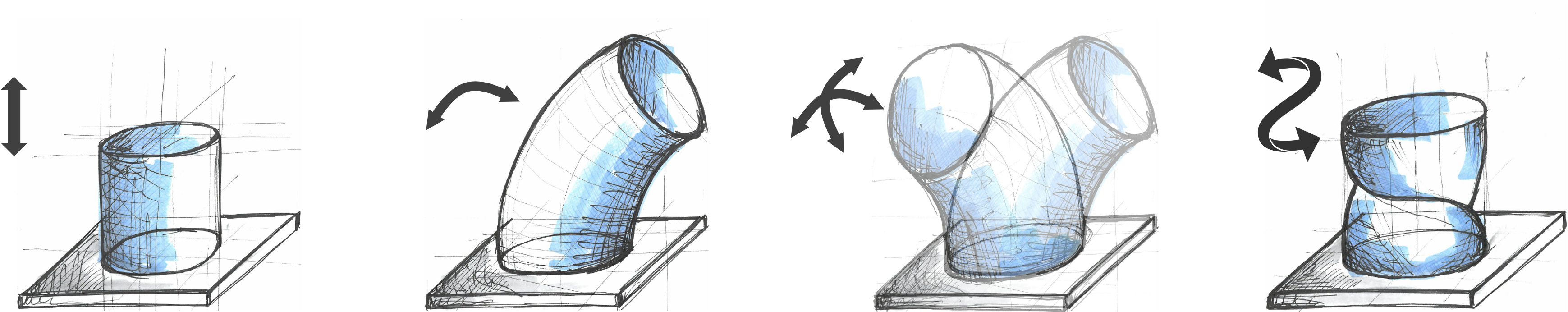

The motion capabilities of a continuum robot can be expressed by a set of motion primitives:

Extension and Contraction to change the length along one axis.

Bending in one plane (i.e. rotation about one axis) or spatially (i.e. rotation about two axes).

Twisting about the longitudinal axis (i.e. turning or torsion)

|

| Motion primitives: change of length, bending in one planar or spatially, and torsion. |

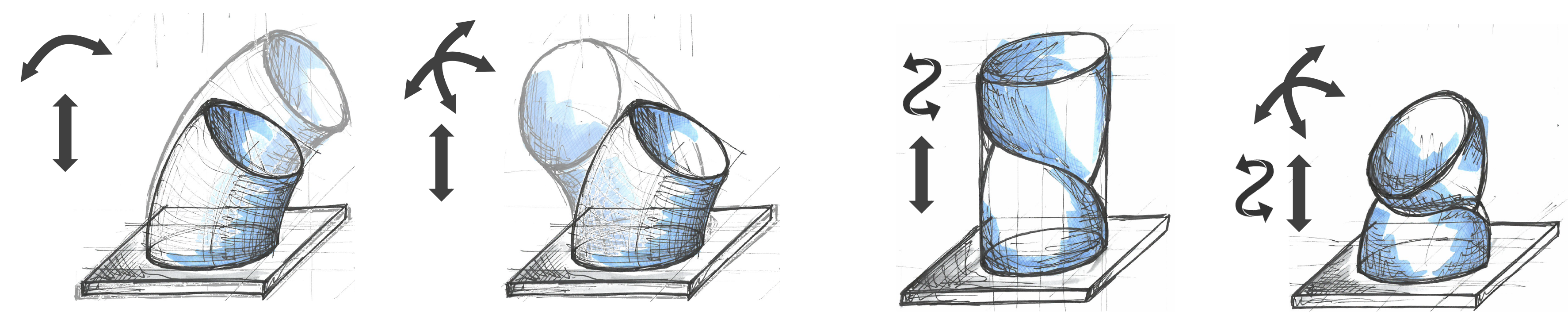

These motion primitives can be combined and realized in a single continuum robot segment. The Figure below shows some examples. For instance, a continuum robot segment can bend in one plane and change its length or bend spatially and change its length.

|

| Examples of motion capabilities for a single continuum robot segment. |

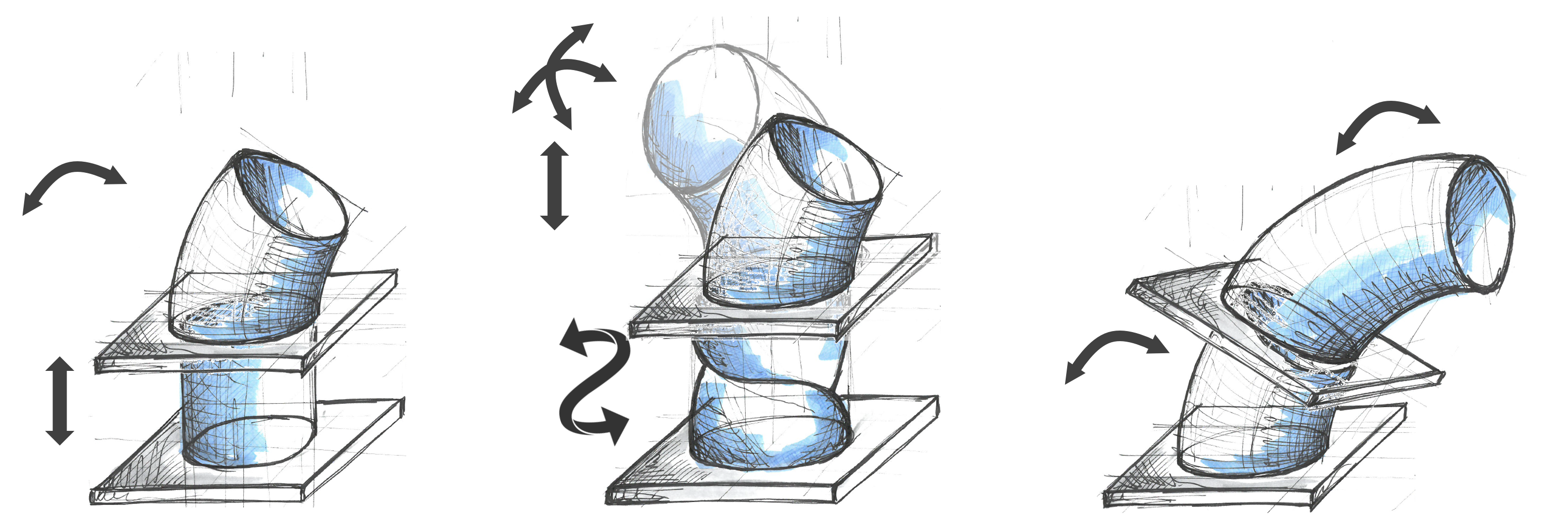

To increase the range of motion of a continuum robot, we can stack multiple of these segments, i.e. arrange them in series.

|

| Composing a continuum robot of multiple segments. |

Note

The backbone of a continuum robot does not necessarily have to be continuous. The biological counterpart, e.g. snakes, have a continuous external appearance, but are vertebrates with an internal segmented backbone comprised of many very short rigid-links.

A similar paradigm can be applied to compose a discrete continuum robot. As in a serial robot arm, this can be achieved by concatenating multiple links connected by revolute joints. By keeping the link length short, the appearance of such a serial robot arm is resembling a continuous structure. In robotics, this type of robot is commonly referred to as a hyper-redundant robot, as it exhibits a high number of degrees of freedom in joint space. Those highly hyper-redundant robots can also be referred to as quasi-continuous or pseudocontinuum.

Further Reading: Wondering how one could design a continuum robot that had extension/contracting, bending, and twisting all in one? We recently introduced FAS - A fullt actuated segment for tendon-driven continuum robots1.

References

-

R.M. Grassmann, P. Rao, Q. Peyron, J. Burgner-Kahrs: FAS—A Fully Actuated Segment for Tendon-Driven Continuum Robots. Frontiers in Robotocs and AI, 9:873446, 2022. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2022.873446 ↩