Continuum Robotics 101

We are starting our 101 blog post series. In this category, we will present introductory concepts in continuum robotics targeted at novices who have prior knowledge in fundamental robotics and in serial manipulators. The material is based off the Continuum Robotics course I taught at Leibniz University Hannover in 2017 and 2018 and the Introduction to Continuum Robotics I am teaching at the University of Toronto since 2021.

Today, we are looking at two questions

How can we identify a continuum robot? What differentiates continuum robots from other robot types?

When thinking about a robot, what comes to our minds are usually manipulator arms, i.e., serial robot arms, performing repetitive tasks in automation and manufacturing, or humanoid robots, i.e., human-like walking robots interacting with their environment in everyday tasks. Those robots are inspired by the human anatomy as they resemble a similar structure in terms of rigid-links and joints. These rigid-link robots usually have similar degrees-of-freedom as their human counterpart. Naturally, the tasks and use cases are those that a human would typically do, such as welding, moving objects, etc., but with the additional speed and repeatability of a robot. Another typical robot type is mobile platforms, i.e., wheeled robots. A prominent example is a vacuum cleaning robot that many of us might deploy in our homes.

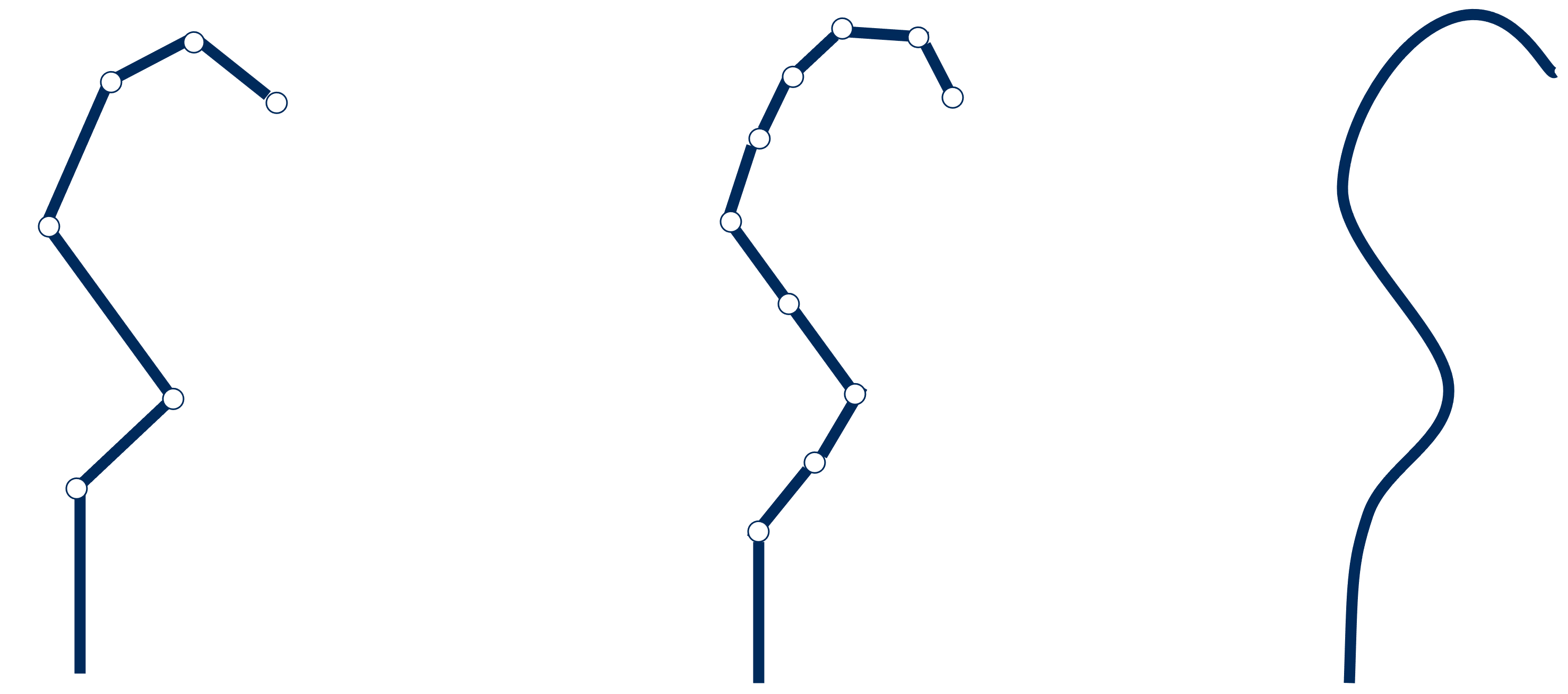

Robotics is revolutionizing automation in the manufacturing sector. The World Robotics 2021 Industrial Robots report shows a record of 3 million industrial robots operating in factories around the world – an increase of 10%! Robotics also found its way out of the factory into the service domain, where it has already had a significant impact in areas such as medicine, logistics, or agriculture and is growing in economic impact. Beside the general market trends in manufacturing and service robotics, there exist applications which are characterized by hard-to-reach areas, tortuous paths, and highly unstructured environments, for instance intracorporal or intraluminal medical applications, non-destructive inspection or in maintenance, repair and operation (MRO). These applications mostly require highly dexterous and miniaturized robots. Intuitively, one would increase the number of discrete joints and reduce the length of the rigid-links in order to increase the DOF in task space. The robot is then referred to as redundant. The more joints one adds and the shorter the link length in between these joints becomes, the robot structure becomes hyperredundant (see figure above). However, the discrete structure of rigid-links connected by joints cannot be miniaturized to any arbitrary size. In fact, the integration of mechatronic components reaches physical miniaturization limits.

To overcome these limitation, there has been a paradigm shift away from rigid-link, discrete structures to continuously bending ones. These are commonly referred to as continuum robots. Continuum robots differ fundamentally from traditional robots, as they are jointless structures. Their appearance is evocative of animals and organs such as trunks, tongues, worms, and snakes. Composed of flexible, elastic, or soft materials, continuum robots can perform complex bending motions and appear with curvilinear shapes.

Continuum robots have a high potential to navigate and operate in confined spaces currently unreachable to standard robots, as their diameter to length ratio can be quite low. These robots are usually developed to reach sites of interests through complex and winding trajectories, in contrast to either standard mechanical tools or stiff serial robots.

Four Examples

Before formally defining a continuum robot, we look at three commercially available and one continuum robot on the verge to being commercially available, to illustrate how continuum robots look like and what they can do.

Example 1: Bionic Motion Robot

The company FESTO has been pioneering continuum robots at comparable size to collaborative serial robot arms. Here, we see the latest version of their pneumatically actuated continuum robot called the Bionic Motion Robot. Consisting of three concatenated segments, each of which consists of three elastomer bellows, it can extend/contract and bend by changing the pressure within the bellows. With a diameter of 13cm and length of 85 cm, the Bionic Motion Robot weighs about 3kg and can also carry about 3kg. The Bionic Motion Robot is advertised for collaborative tasks with humans as it is light-weight and safe, e.g. in assembly.

Example 2: Snake-arm Robot

The snake-arm robot developed by OCRobotics is probably the longest among all continuum robots with 5m length. The snake-arm robot is driven by wire ropes guided through channels on the circumference of the cylinders composing the robot structure. Two wire ropes terminate at each cylinder along the robot, forming the links. As a result, by pushing/pulling on a wire rope, the respective segment can bend up to 27.5 degrees. At a diameter of 12.5cm and overall length of up to 5m (3m of which are articulated) the robot has a payload of up to 10kg. OCRobotics has been acquired by GE Aviation in 2017 to move the technology towards use in aviation industry for repair and operations.

Example 3: Multi-articulated Instruments

The multi-articulated instruments developed by Titan Medical Inc. are following a comparable actuation mechanism as the snake-arm robot. To achieve bending into an S-curve the instrument is composed of two segments each of which are driven by four wires terminating at their end. Pushing or pulling on the wire pairs achieves bending in all directions. These multi-articulated instruments are part of a surgical robot system intended for use in single-port interventions, i.e. entering the human body through a single incision. The instruments are teleoperated by the surgeon, i.e. the motion of the instruments is commanded via an input device at the surgeon’s console. The system is not yet commercially available.

Example 4: Soft Finger Gripper

Using continuously bending structures to realize grippers for industrial automation applications has advantages over conventional 2- or 3-claws grippers when a wide range of objects need to be handled which are delicate or amorphous (e.g. food). One example of such a soft gripper is commercially available from Soft Robotic Inc. Each finger is composed of a soft silicone and resembles an accordion. Actuation is achieved by pneumatics: changing the pressure results in bending of a finger. The fingers can be arranged in a parallel or circular pattern depending on the objects to be handled.

Note: Examples 1 and 2 are showing continuum robots comparable in size to conventional serial arm robots, while Examples 3 and 4 show smaller scale continuum robots. High dexterity and continuously bending is particularly useful at small scales as this is where conventional serial arm robots fail due to miniaturization constraints. As continuum robotics is an artive area of research, we have not yet seen too many continuum robots being available in commercial products.

Definition

Researchers in the continuum robot community have not yet converged to a single definition, such that there exist three major definitions, which are stated in chronological order.

The very first formal definition of continuum robots as a class of robots was proposed by Robinson & Davies1 in 1999:

Continuum robots do not contain rigid links and identifiable rotational joints. Instead the structures bend continuously along their length via elastic deformation and produce motion through the generation of smooth curves, similar to tentacles or tongues of the animal kingdom.

The definition focusses on the appearance of continuum robots and puts continuous bending and elastic deformation as key characteristics. It also explicitly excludes rigid links and identifiable joints, such that snake-like robot structures as in Example 2 would formally not qualify for a continuum robot based on this definition.

Defining a continuum robot by relating its kinematic structure to the animal kingdom was proposed by Walker2 in 2013:

Continuum robots can be viewed as being invertebrate robots, as compared with the vertebrate design of conventional rigid-link robots. Continuum robots can bend (and often extend/contract and sometimes twist) at any point along their structure.

This definition follows the formalism of invertebrates, i.e. animals without a backbone or bony skeleton. According to this, continuum robots have no rigid links and joints as well. Interestingly, the structure of a continuum robot is often referred to as its backbone - even though it is continuous. In comparison to Robinson & Davies definition, Walker’s definition explicitly includes extension and contraction as a characteristic of continuum robots.

To mathematically formalize the existing definitions, Burgner-Kahrs, Rucker & Choset3 propose the following definition:

A continuum robot is an actuatable structure, whose constitutive material forms curves with continuous tangent vectors.

This definition generalizes the previous two in that sense that it does not make assumptions on how the continuum robot is actuated nor on the elasticity of the composing materials, but requires the representation of the morphology to be a continuous curve.

The boundary that separates continuum robots from other snake-like or hyper-redundant manipulators is sometimes obscured by manipulator designs that use continuously bending elastic elements along with conventional discrete joints in the same structure. While these robots may not technically be classified as continuum robots according to the definitions, they are referred to as pseudo-continuum robots or hybrid serial/continuum robots, as they are closely related to continuum robots and share many attributes with them.

Summary

Continuum robots are a type of robot which is characterized by its absence of rigid-links and joint and continuous appearance. The motivation behind building continuum robots is that they have certain abilities which make them distinct from other robots:

- Inherent compliance and flexibility

- Ability to perform new forms of robot motion and locomotion

- Miniaturization

- Adapt shape to maneuver within complex, tortuous environments

- Ability to avoid obstacles

- Conform to grasp wide range of objects

These abilities make continuum robots ideal candidates for a variety of applications which can typically not be performed with conventional robots. For instance, in medicine for use in surgical robotics (neurosurgery, urological surgery, lung surgery, etc.) or interventions (cardiovascular or neuroendovascular surgery, bronchoscopy, endoscopy, colonoscopy). Or in maintenance, repair, and operations of capital goods such as jet-engines, or non-destructive testing and inspection such as for cracks or corrosion in oil and gas and petrochemical industries.

References

-

G. Robinson and J.B.C. Davies: Continuum robots - a state of the art. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 1999, pp. 2849-2854 vol.4, doi: 10.1109/ROBOT.1999.774029. ↩

-

I.D. Walker: Continuous Backbone “Continuum” Robot Manipulators. ISRN Robotics, 2013, pp.1–19. doi: 10.5402/2013/726506 ↩

-

J. Burgner-Kahrs, D.C. Rucker and H. Choset: Continuum Robots for Medical Applications: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 31(6), pp.1261–1280. doi: 10.1109/TRO.2015.2489500 ↩